Database Migrations

Table of Contents

I consider database migrations one of the most annoying problems to deal with during a software engineer’s life. Not only that, if it goes wrong, as it often does, people tend to develop anxiety related to any schema changes.

So why is it so annoying? It looks simple at first glance but is deceptively tricky when you start thinking about it.

My primary framework of choice is the Python-based Django, which released schema migrations over a decade ago and which I still consider one of the best migration engines that I’ve seen. (and I worked with many different frameworks across many languages).

But even with an excellent framework that automatically generates migration files, stores the migration references in the database, and allows for easy rollbacks — there are a ton of things to consider when you do database migrations.

Imagine a novel approach for splitting up the ‘name’ field into 'first_name’ and ‘last_name’ in the user Table. All is going fine. You do the schema migration, run the migration script of splitting old data into two fields, and deploy the latest API that works with these changes. Still, something goes wrong with the new fields. Your monitoring shows many unique users with failed saved due to some validation error, e.g., not all characters are being accepted. This issue is deemed critical, so you and the team decide to do a rollback. Sounds good. You revert the schema migration and revert the app to the previous state, but then you notice that writes were happening to the new fields during that small window of deployment, and now some users have missing data in the name field, which leads to data inconsistency.

And now add more complexity with the requirement of doing all that with zero downtime.

🏄 This example is hypothetical, but what I’m trying to say is that database migrations are complex problems that should be approached with a multi-step process. I also can relate to those who really don’t want to approach such problems — it’s a tedious process where you need to verify the data constantly.

So I’ve mentioned that the data migrations are hard, and nobody wants to work with them, but why? Here are a few reasons:

- When developing a product, you can only see a few months, maybe a year in advance, how the software will evolve and how you can prepare for that. A year into the future, a product owner might come to you and say, “Okay, our financial app is no longer based on transactions; everything is a subscription,” — which is obviously a huge database migration to fit the case (or build workarounds).

- Doing migrations is like working with live wires. You have a new Lamp that you need to hang on the ceiling, but you’re doing that without turning off electricity. I took the Lamp as an example because I hung one yesterday, so it came to mind.

- Every migration that you’re implementing (and yes, you need to think of migrations as code, not just database changes) needs to work with three different scenarios:

- Upgrading (Migrating up) - new feature gets built, data model gets added/changed/removed. The new and old application versions are still expected to function as expected.

- Downgrading (Migrating down) - Something went wrong, there are data inconsistencies — you need a way to go back to the previous stable state in a controlled manner. Not with manual changes in the DB.

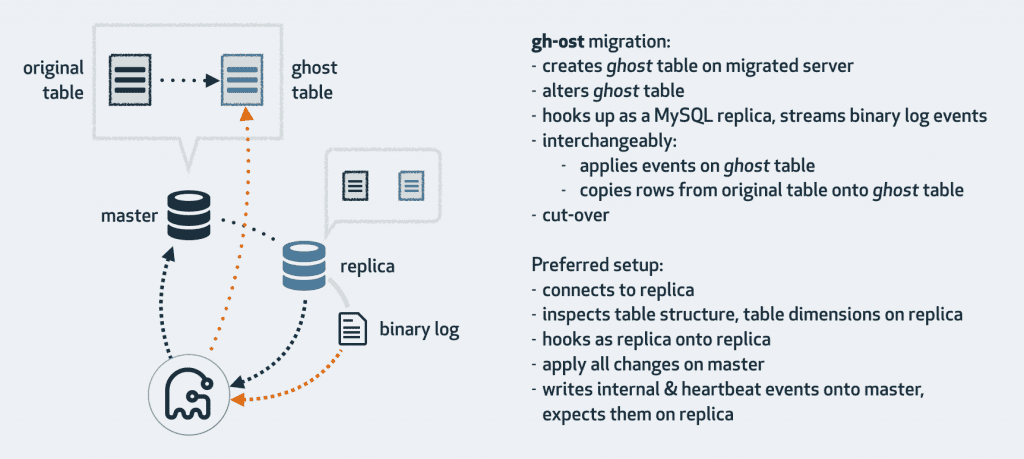

- Everything in between - meaning all the data transformation logic needs to be taken care of. Though nowadays, there are many ways to do the data transformation over more extended periods of time with dual writes or a concept of “ghost tables” with the help of the gh-ost library from Github; we will talk about this later.

- Data migrations are also problematic because it’s usually not a one-person job. The bigger the data model change, the more people should be involved. It would be best to have different people on standby when deploying, ready to jump in WHEN things go wrong. I wrote when because it’s highly likely that something will not go as planned on at least one of the steps.

Simple Deployment

Here’s the most straightforward approach that you can take with deploying a new feature that has database changes in it, that is, if you’re small enough and can allow yourself to have a few seconds of downtime:

- Push your code to Bitbucket/Github/Gitlab.

- Deployment gets triggered.

- New docker containers get built

- Database migrations and all the related scripts are run

- Docker containers are restarted on the server

I’ve seen a lot of hate for this simple approach, but I’ve got to say, it’s fine. The deployment doesn’t need to be a headache until you reach a level where zero downtime is business-critical.

The approach above is absolutely valid if:

- You have a single application instance.

- You can allow yourself a few seconds of downtime.

- You’ve already tested the migrations on staging.

This is not a valid approach if:

- You’re running multiple app instances, which might result in a race condition for the migrations and an invalid database state.

- You have lots of data and need to transform it — which will block the deployment process or possibly timeout.

- Downtime is not an option.

Now that we’ve cleared up the most straightforward approach on deploying the changes, let’s look at some different migration scenarios you’ll have to deal with during your career as a software engineer.

Scenarios

Adding a New Field

This is the easiest case, as adding a field to a database is basically a no-op from the perspective of your app and should not impact the current logic in any way. The new field will be accessed and used only once the new application gets deployed.

After adding the field to your ORM, generate an immutable migration script. Test this script locally to ensure it behaves as expected. Forwards and backward migrations should be tested. Don’t forget to add fixtures to your tests for your new data.

If the new field is non-nullable, provide a default value. This is crucial to avoid issues with existing records that won't have this field populated. If logic is involved, e.g., the field is an aggregate of other fields — add the logic to the migration script. (I mention below why this concept only works for databases with low volume ~ a few million rows and won’t work for large databases.)

Focus on the 2-phase deployment approach. First, deploy the database changes. As adding a new field should not break any changes in your app, this should run smoothly even with the current version of the app. Once you're confident that the migration has been successful and hasn't introduced any issues, deploy the application changes.

After deployment (also before), monitor the application and database performance. Look out for any unexpected behaviors related to your new field.

Now, let’s go back to the non-nullable fields with defaults. Here's why default values can be particularly problematic for large datasets:

- Immediate update of all rows - once you add a new column with a default value, most DBs will need to update every row with that value. With billions of rows, that might take a while.

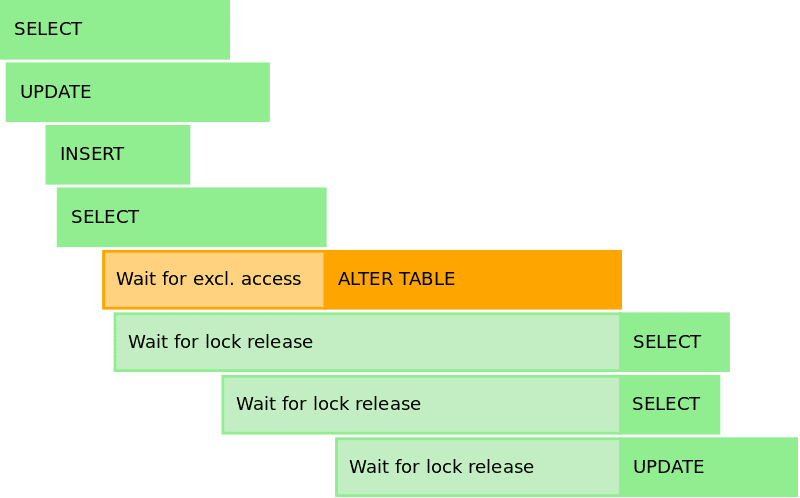

- The “ALTER TABLE” command requires a “LOCK” on each table as long as the migration operation is not finished. (Since the latest version of Postgres, this is no longer true for adding new fields with default, but still true for changing fields, as it updates the metadata.) This LOCK is exclusive and does not allow more writing on the relations being modified.

- If you have replicas and billions of rows - they will start lagging behind.

Removing a Field

Now we’re getting slightly into more complicated stuff, as you’re removing something already being used in the application, so the approach here is somewhat different.

The first step happens long before the database migration happens. Marking/highlighting the code that uses the “field-to-be-removed.” After all the places are marked, start with phasing out the use of that field in the application — first, with commenting out.

🏄 (Optional) Before physically removing a field, consider if the data in that field might be needed in the future. If so, archive this data in a different location.

If, in the first example, we deployed the database changes first, in this case, we begin by deploying the application changes that no longer use the field. Ensure the application is stable with commented-out use of the deleted field. Then, deploy the database migration to remove the field. This two-step process ensures no attempts to access the field after it's removed.

Our focus is to avoid data inconsistency at all costs, so if you deploy the application changes and see the field still getting updated — you missed something.

Enjoyed the read? Join a growing community of more than 2,500 (🤯) future CTOs.

Changing Field with business logic attached

Now we’re getting to the good stuff. Changing a field intertwined with business logic is one of the most intricate migration scenarios. Similar cases include splitting a field from one table into several fields in a new table and moving the data to a different database altogether. All of these cases are similar in how they must be handled.

These are probably the cases that people try to avoid and find workarounds. The reason is — the implications of such changes can ripple through various (unknown to you) parts of the application. That’s why this case:

- should be handled as a team

- should be handled with a dual-write logic

- should be handled with multi-phased deployment (that helps keep everything running with zero data inconsistency)

Before any coding is done — understand the full scope of the change. Identify all relevant read paths in the application and mark them as soon-to-be deprecated.

Refactoring all code paths where we mutate subscriptions is arguably the most challenging part of the migration. Stripe’s logic for handling subscriptions operations (e.g. updates, prorations, renewals) spans thousands of lines of code across multiple services.

- Article Stripe Subscription Migrations, link below

The key to a successful refactor will be our incremental process: we’ll isolate as many code paths into the smallest unit possible so we can apply each change carefully.

Our two tables need to stay consistent with each other at every step.For each code path, we’ll need to use a holistic approach to ensure our changes are safe. We can’t just substitute new records with old records: every piece of logic needs to be considered carefully.

As you can see from the Stripe example, a lot of preparation happens before the migration starts. The code paths are identified and refactored to support dual writes/reads.

What dual-write migration means can be essentially split up into these steps:

- Add the new field to the database (Zero impact on the running code).

- Deploy new, refactored application code, where you start writing to both old and new fields, with the corresponding new business logic applied. Reading is still done from the old path. Writing to both fields must happen as part of a single Transaction.

- Compare the data and make sure it’s consistent.

- Write migration code that transforms the rest of the data from the old field into the new field in the correct format. (Or use gh-ost from Github)

- Deploy the migration and change the read path to the new field. The write path is still to both fields.

- Verify the application and the data consistency.

- Remove writing to the old field. At this point, reading/writing happens exclusively in the new field. The old field still exists in the database but should receive no writes.

- Verify the application and the data consistency.

- Remove any code related to the old field.

- Verify the application and the data consistency.

- Deploy migration script to drop the column from the database.

- Shake hands with your teammates.

I hope this detailed breakdown helps you visualize the flow of executing complex database changes. Each step can be rolled back individually, offering greater stability than making all changes at once. This approach not only reduces the likelihood of errors but also ensures that if mistakes do occur, they can be rectified without any data loss or inconsistencies.

Mobile app + database migrations

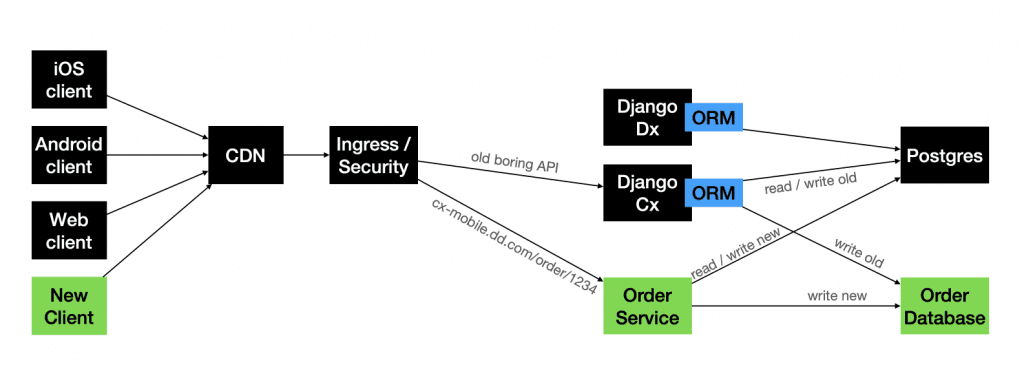

While researching the topic, I stumbled on a talk about how DoorDash split their Postgres database into several smaller ones, and they suggested a different approach (A variation of dual-writing)

As DoorDash is a mobile application, the old versions of the app are still in use when they release a new version. Hence, a database migration becomes a big issue as you must be backward compatible with the data coming from many older app versions.

They tried different versions of dual-write and a surprising third approach:

- API Based Dual Write - API wrapper around the old Service and the new Service

- Database-Based Dual Write - Same API, but writes/reads are triggered to two different databases

- New app version + New Endpoint + New Database - New Application version with a different endpoint that reads/writes to different databases based on old/new logic. This can be called an App-Level Dual-write, as the new app version defines where the old/new data will go.

I find it fascinating how other companies do complex database changes, so I would highly suggest reading some more articles on this topic:

- Stripe Case: Migrating Subscriptions

- Facebook Case: Migrating Messenger

- Gusto Case: Migrating Waivers

- Box Case: Moving from HBase to Google BigTable

Zero downtime

Let’s talk more about zero downtimes.

Not all applications, especially those serving a global audience, have the luxury of a maintenance window. For global platforms like Google, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Netflix, there's no "off-peak" time. The sun never sets on their user base, making any downtime detrimental to user experience and revenue. If one of these goes down - it’s usually the #1 story on HackerNews.

I’m sometimes surprised by emails from payment gateway providers stating they will have a maintenance window next week. That’s basically telling your customers you will not be getting any money during this time… sorry for that.

I’m trying to say that the bigger you are, the more business-critical your service becomes, the less maintenance time you get. If there’s no maintenance window - zero downtime is the only way. Yes, they often take longer because they're deployed in multiple phases to ensure that at no point is the service interrupted. But this phased approach, while highly time-consuming, is a necessary trade-off to ensure service continuity and, more importantly, data consistency.

However, not all of the services are business critical, and the primary reason for downtime for non-Google level companies is the failure to maintain code backward compatibility with their new changes and long-running db migrations.

If you don’t have huge teams of SREs to help you with your deployments, I’d suggest making your life just a tiny bit better with some tools that allow instant, non-blocking schema changes as well as ghost tables for data migrations:

- if you’re on MySQL — consider using framework agnostic gh-ost from Github or MySQL Online DDL or pt-online-schema-change or Facebook OnlineSchemaChange which works in a similar way to gh-ost.

- if you’re on Postgres and are using Django — try out the django-pg-zero-downtime-migrations or Yandex zero-downtime-migrations also here are some HN comments about the library.

- There's also SchemaHero — an open-source database schema migration tool that converts a schema definition into migration scripts that can be applied in any environment.

Conclusion

Let’s wrap up the article with some best practices:

- No manual database changes. Always generate immutable migration scripts.

- Database version should be contained in the database itself. (Django does this automatically)

- If you don’t have maintenance windows — focus on the dual-write process.

- When building features with significant database changes - think of backward compatibility and correct abstractions.

- Consider using the latest tools to make your migration life easier.

- What else? Suggest some in the comments :)

References:

https://gist.github.com/majackson/493

https://pankrat.github.io/2015/django-migrations-without-downtimes/

https://enterprisecraftsmanship.com/posts/database-versioning

https://habr.com/ru/articles/664028/

https://www.martinfowler.com/articles/evodb.html

https://dev.to/kite/django-database-migrations

https://teamplify.com/blog/zero-downtime-DB-migrations/

https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=22698154

https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=16506156

https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=27473788

https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=19880334

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/1482738/how-is-database-migration-done

Other Newsletter Issues:

-

Anonymous

Mike wrote about this a few years ago. It is a super hard problem. https://cacm.acm.org/blogcacm/database-decay-and-what-to-do-about-it/

-

Ojas

I always break down database migrations into smaller chunks to lessen the headache. Testing in a staging environment before going live has saved me from countless panic-inducing moments.

-

Anonymous

I would consider mentioning in the reference section the Refactoring Databases book, https://martinfowler.com/books/refactoringDatabases.html

-

Ben Peikes

MySQL supports no lock column additions now.

-

Anonymous

You may find the Refactoring Databases book interesting to read.

-

Anonymous

For zero downtime on Postgres, there is also https://github.com/shayonj/pg-osc

-

ChoHag

You don’t get zero downtime. You can get close, but every 9 you add to your 99.9…% uptime costs an order of magnitude more. The gold standard of 5 9s or 99.999% uptime gives you about 8 mintues of maintenance per year and costs around 3 sysadmins for a small to medium system.

Your maintenance, or downtime, will happen whether you plan for it or not.

-

Martin Omander

Great all well through-out article!

Some teams can get the best of both worlds by picking a middle ground between “significant downtime” and “zero downtime”. That’s because many applications are still useful when in read-only mode.

I recently did such a migration in a NoSQL database that supports hundreds of thousands of users per day. Instead of doing all the engineering work to enable “zero downtime”, I put the application in read-only mode for two hours. The application still worked for most users, and it bought me time to copy data from the old to the new tables. Then I deployed new code which did dual-write and compared the old and new tables for every read. After a week of no major problems, I switched over to the new table for all reads and writes.

-

Dima

For Rails and PostgreSQL users – https://github.com/fatkodima/online_migrations

-

Anonymous

Nice writeup. Please also take a look at Bytebase, which is the GitLab/GitHub for database (Disclaimer, I am one of the authors)